How to Code Neat Machine Learning Pipelines

Coding Machine Learning Pipelines - the right way.

Have you ever coded an ML pipeline which was taking a lot of time to run? Or worse: have you ever got to the point where you needed to save on disk intermediate parts of the pipeline to be able to focus on one step at a time by using checkpoints? Or even worse: have you ever tried to refactor such poorly-written machine learning code to put it to production, and it took you months? Well, we’ve all been there if working on machine learning pipelines for long enough. So how should we build a good pipeline that will give us flexibility and the ability to easily refactor the code to put it in production later?

First, we’ll define machine learning pipelines and explore the idea of using checkpoints between the pipeline’s steps. Then, we’ll see how we can implement such checkpoints in a way that you won’t shoot yourself in the foot when it comes to put your pipeline to production. We’ll also discuss of data streaming, and then of Oriented Object Programming (OOP) encapsulation tradeoffs that can happen in pipelines when specifying hyperparameters.

What are pipelines?

A pipeline is a series of steps in which data is transformed. It comes from the old “pipe and filter” design pattern (for instance, you could think of unix bash commands with pipes “|” or redirect operators “>”). However, pipelines are objects in the code. Thus, you may have a class for each filter (a.k.a. each pipeline step), and then another class to combine those steps into the final pipeline. Some pipelines may combine other pipelines in series or in parallel, have multiple inputs or outputs, and so on. We like to view Machine Learning pipelines as:

- Pipe and filters. The pipeline’s steps process data, and they manage their inner state which can be learned from the data.

- Composites. Pipelines can be nested: for example a whole pipeline can be treated as a single pipeline step in another pipeline. A pipeline step is not necessarily a pipeline, but a pipeline is itself at least a pipeline step by definition.

- Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAG). A pipeline step’s output may be sent to many other steps, and then the resulting outputs can be recombined, and so on. Side note: despite pipelines are acyclic, they can process multiple items one by one, and if their state change (e.g.: using the fit_transform method each time), then they can be viewed as recurrently unfolding through time, keeping their states (think like an RNN). That’s an interesting way to see pipelines for doing online learning when putting them in production and training them on more data.

Methods of a Pipeline

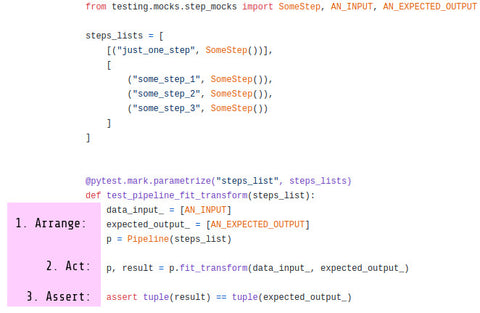

Pipelines (or steps in the pipeline) must have those two methods:

- “fit” to learn on the data and acquire state (e.g.: neural network’s neural weights are such state)

- “transform” (or “predict”) to actually process the data and generate a prediction.

Note: if a step of a pipeline doesn’t need to have one of those two methods, it could inherit from NonFittableMixin or NonTransformableMixin to be provided a default implementation of one of those methods to do nothing.

It is possible for pipelines or their steps to also optionally define those methods:

- “fit_transform” to fit and then transform the data, but in one pass, which allows for potential code optimizations when the two methods must be done one after the other directly.

- “setup” which will call the “setup” method on each of its step. For instance, if a step contains a TensorFlow, PyTorch, or Keras neural network, the steps could create their neural graphs and register them to the GPU in the “setup” method before fit. It is discouraged to create the graphs directly in the constructors of the steps for several reasons, such as if the steps are copied before running many times with different hyperparameters within an Automatic Machine Learning algorithm that searches for the best hyperparameters for you.

- “teardown”, which is the opposite of the “setup” method: it clears resources.

The following methods are provided by default to allow for managing hyperparameters:

- “get_hyperparams” will return you a dictionary of the hyperparameters. If your pipeline contains more pipelines (nested pipelines), then the hyperparameter’ keys are chained with double underscores “__” separators.

- “set_hyperparams” will allow you to set new hyperparameters in the same format of when you get them.

- “get_hyperparams_space” allows you to get the space of hyperparameter, which will be not empty if you defined one. So, the only difference with “get_hyperparams” here is that you’ll get statistic distributions as values instead of a precise value. For instance, one hyperparameter for the number of layers could be a

RandInt(1, 3)which means 1 to 3 layers. You can call.rvs()on this dict to pick a value randomly and send it to “set_hyperparams” to try training on it. - “set_hyperparams_space” can be used to set a new space using the same hyperparameter distribution classes as in “get_hyperparams_space”.

Re-fitting a Pipeline, Mini-Batching, and Online Learning

For mini-batched algorithms like for training Deep Neural Networks (DNN), or for online learning algorithms such as in Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms, it is ideal if the pipelines or if the pipeline steps can update themselves on chaining several calls to “fit” one after another, re-fitting on the mini-batches on the fly. Some pipelines and some pipeline steps can support that, however, some other step will reset themselves upon having “fit” called anew. It depends how you coded your pipeline step. It is ideal if your pipeline step only resets upon calling the “teardown” method, then “setup” again before the next fit, and doesn’t reset between each fit nor during transform.

Using checkpoints in your pipelines

It is a good idea to use checkpoints in your pipelines - until you need to re-use that code for something else and change the data. You might be shooting yourself in the foot if you don’t use the proper abstractions in your code.

Pros of using checkpoints in your pipelines:

- Checkpointing can increase coding speed when coding and debugging the steps at the middle or at the end of your pipeline, avoiding to compute the first pipeline steps anew every time.

- When doing hyperparameter optimization (either manual tuning or meta learning), you’ll be happy to avoid re-computing the first pipeline steps when you are tuning the next ones. For instance, the beginning of your pipeline might be always the same if it doesn’t have hyperparameters, or almost the same if it has only a few hyperparameters. Thus, with checkpoints, it’s good to resume from the places where you checkpointed if the hyperparameters and source code of the steps before the checkpoint didn’t change since the last execution.

- You may be limited in computing power, and running one step at a time may be the only tractable option in consideration of your available hardware. You can use a checkpoint, then add more steps after the checkpoint, and the data will be resumed from where you left it off if you re-execute the whole thing.

Cons of using checkpoints in your pipelines:

- It uses disks which can slow down your code if done wrong. At least, you can speed this up by using a RAM Disk, or by mounting the cache folder to your RAM.

- It may require a lot of disk space. Or a lot of RAM space if using a folder mounted in RAM.

- The state saved on disk is harder to manage: there is added complexity to your program for your code to run faster. Note that in functional programming terms, your functions and code won’t be pure anymore, because of the need to manage side effects with the disks. The side effects coming from managing the disk’s state (your cache) may create all sorts of weird bugs. It is known that in programming, some of the hardest bugs are cache invalidation problems.

“There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.” — Phil Karlton

An advice on properly managing state and cache in pipelines.

Programming frameworks and design patterns are known to be limiting by the simple fact that they enforce some design rules. That is hopefully in the goal of managing things for you in an easy way and to avoid yourself making mistakes or ending up with dirty code. Here is my shot at it for pipelines and managing state:

- PIPELINE STEPS SHOULD NOT MANAGE CHECKPOINTING THEIR DATA OUTPUT.

This should be managed by a pipelining library which can deal with all of this for you.

Why?

Why should pipeline steps not manage checkpointing their data output? Well, it’s for all these valid reasons that you’ll prefer to use a library or framework instead of doing it yourself:

- You will have an easy on/of switch to completely enable or disable checkpointing for when you’ll deploy to production.

- When you’ll need to re-train on new data, caching is so well-managed for you that it’ll detect that your data changed, and it will ignore your existing cache by itself, without requiring your interaction, which will avoid important bugs.

- You won’t have to interact with disks by yourself coding Inputs/Outputs (I/O) operations at every pipeline step. Most coders prefer to code the Machine Learning algorithms and to build the pipelines rather than having to code the data serialization methods. Admit it - you just want to code the crunchy algorithms and want the rest done for you. Don’t you?

- You now have the possibility to give a name for each of your pipeline experiments or iterations such that every time you restart, a new caching subfolder is created for this unique occasion - even if reusing the same pipeline steps. And naming your experimentations isn’t even needed as the caching changes if your data changes.

- Your pipeline steps classes inner code are hashed and compared to see if caching needs to be re-done for a class in which you just changed the code to avoid cache invalidation bugs. Hooray.

- You now have the possibility of hashing the intermediate data results and skipping computing the pipeline on this data when the hyperparameters are the same and that your pipeline already transformed (and hence cached) the data earlier. This can ease hyperparameter tuning where sometimes even intermediate pipeline steps may change. For instance, the first pipeline steps may remain cached as it keeps being the same, and if you have more hyperparameters to adjust in the following steps of your pipeline and have more checkpoints later after those steps, then the multi-caching of the intermediate pipeline steps are saved with a unique name computed from the hash. Call this a blockchain if you want, because it is in fact a blockchain.

This is cool. With the proper abstractions, you can now code your Machine Learning pipeline with a huge speed-up when tuning hyperparameters by caching every trial’s intermediate result, skipping steps of the pipeline trial after trial when the hyperparameters of the intermediate pipeline steps are the same. Not only that, but once you’re ready to move the code to production, you can now disable caching completely without having to try to refactor code for a month. Avoid hitting that wall.

Data Streaming in Machine Learning Pipelines

In parallel processing theory, pipelines are taught to be a way to stream data such that a pipeline’s steps can all run in parallel. The laundry example is good at picturing the problem and the solution. For example, a streaming pipeline’s second step could start processing partial data out of the first pipeline’s step while the first step still computes more data, and without having for the first pipeline’s step to completely finish processing all the data. Let’s call those special pipelines streaming pipelines (see streaming 101, streaming 102).

Don’t get us wrong, scikit-learn pipelines are nice to use. However, they don’t allow for streaming. Not only scikit-learn, but most machine learning pipelining libraries out there don’t make use of streaming whereas they could. The whole python ecosystem has threading problems. In most pipeline libraries, each step is completely blocking and must transform all the data at once. There are just a few which enable streaming.

Enabling streaming could be as simple as using a StreamingPipeline class instead of a Pipeline class to chain steps one after the other, providing a mini-batch size and a queue size between steps (to avoid taking too much RAM, which makes things stable in production environments). The whole would also ideally require threaded queues with semaphores as described in the producer-consumer problem to pass info from one pipeline step to another.

One thing that Neuraxle does already better than scikit-learn is to have sequential pipelines, which can be used by using the MiniBatchSequentialPipeline class. The thing is not threaded yet (but it is well in our plans). At least, we already passes the data to the pipeline in mini-batches during fit or during transform before collecting results, which allows for big pipelines using pipelines like the ones in scikit-learn but here with mini-batching. And with all our extra features like hyperparameter spaces, setup methods, automatic machine learning, and so forth.

Our Solution for Parallel Data Streaming in Python

- The fit and/or transform method can be called many times in a row to improve the fit with new mini-batches.

- Using threaded queues inside the pipeline as in the producer-consumer problem. One queue is needed between each pipeline steps that are streamed. If many steps in a row do

- It is possible to allow for parallel replication of pipeline steps to transform multiple items in parallel at each step. This can be done before the

setupmethods are called throughout the pipeline. Otherwise, the pipeline needs to be serialized, cloned, and reloaded with pipeline step savers, which is something we already coded and would be ready for use. Code that uses TensorFlow and other imported code that was build in other languages such as C++ is hard to thread in Python, especially when it uses GPU memory. Even joblib can’t fix easily some of those issues. Avoiding that with proper serialization is good - A parameter of the pipeline could be whether or not it is important to keep the data in the good order before sending it to the next step. By default it would be, and if not, the pipeline can continue processing data in random orders as it comes if some steps takes variable amounts of time.

- It will be possible to make use of barrier objects between some steps in the pipeline. They would not be real steps, but rather, ways to specify to the pipeline how to treat the data between the steps, such that the data must or must not retain its order at some key places. For example, you could use in-order barriers, out-of-order barriers, or even wait-for-all blocking barriers (a Joiner). We already have coded the Joiner. Those barriers add information on how to process the data between the steps or groups of steps. For instance, it can specify or override the pipeline’s length of one specific queue and the number of times to run a pipeline step in parallel and how to parallelize that step.

- We also plan to code repeaters and batch randomizers that will be able to repeat each training data example a few times, which is common when training neural networks.

Not only that, but the way to make every object threadable in Python is to make them serializable and reloadable. That said, in Neuraxle we plan to very soon code this. It will allow for dynamically sending code to be executed remotely on any worker (that it be another computer or process), even if that worker doesn’t have the code itself. This is done with a chain of serializers that are specific to each pipeline step class. By default each of those steps has a serializer that can handle regular Python code, and for more wicked code using GPUs and import code in other languages, models are just serialized with those savers, and then reloaded on the worker. If the worker is local, objects can be serialized to a RAM disk or a folder mounted in RAM.

Encapsulation tradeoffs

There is one thing that still annoys us in most machine learning pipeline libraries. It is how hyperparameters are treated. Take for example scikit-learn. Hyperparameter spaces (a.k.a. statistical distributions of hyperparameters’ values) must often be specified outside of the pipeline with underscores between each steps of steps or each pipeline of pipeline, and so on. While the Random Search and the Grid Search can search hyperparameter grids or hyperparameter probability spaces such as defined with scipy distributions, scikit-learn does not provide a default hyperparameter space for each classifier and transformer. This could be the responsibility of each object of a pipeline. This way, an object is self-contained and also contains its hyperparameters, which doesn’t break the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) and the Open-Closed Principle (OCP) of the SOLID principles of Object-Oriented Programming (OOP). Using Neuraxle is a good solution to avoid breaking those OOP principles.

Compatibility and Integration

A good thing to keep in mind when coding machine learning pipelines is to have them be compatible with lots of things. As of now, Neuraxle is compatible with scikit-learn, TensorFlow, Keras, PyTorch, and many other machine learning and deep learning libraries.

For instance, neuraxle has a method .tosklearn() which allows the steps or a whole pipeline to be made a scikit-learn BaseEstimator - that is, a basic scikit-learn object. For other machine learning librairies, it’s as simple as creating a new class that inherits from Neuraxle’s BaseStep, and override at least your own fit, transform, and perhaps also the setup and teardown methods, and defining a saver to save and load your model. Just read BaseStep’s documentation to learn how to do that, and also read the related Neuraxle examples in the documentation.

Conclusion

To conclude, writing production-level machine learning pipeline requires many quality criterias, which hopefully can all be solved if using the good design patterns and the good structure in your code. To sum up:

- It’s a good thing to use pipelines in your machine learning code, and to define each step as a pipeline step “BaseStep” for instance.

- Then, the whole thing can be optimized with checkpoints when searching for the best hyperparameters and re-executing the code on the same data (but perhaps with different hyperparameters or with changed source code).

- It’s also a good idea to fit and transform data sequentially not to blow RAM. Then, the whole thing can also be parallelized when switching from a sequential pipeline to a streaming pipeline.

- You can finally also code your own pipeline steps, you just have to inherit from the BaseStep class and implement the methods you need.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Vaughn DiMarco for brainstorming on this with me and motivating me to write this article. Also thanks to our contributors, clients and supporters who openly supports the project.

The future is now. If you’d like to support this project too, we’ll be glad that you get in touch with us. You can also register to our updates and follow us.